Monday, December 24, 2012

Wednesday, December 19, 2012

When You Care Enough...

I can’t escape some stories. You know the ones. Those tragic tales of antique vehicle neglect, oversight or just a plain lack of understanding that allows a piece to deteriorate… those accounts can make us all cringe. Not long ago, I had another person share about an early horse-drawn wagon he had purchased that – at least when he first saw it – still retained a significant amount of original paint. The seller, though, thinking he would do the buyer a favor, decided to ‘clean’ the wagon up a bit before the buyer arrived. Taking a high pressure water hose, he blasted the entire vehicle. Of course, once the buyer arrived to pick up the purchase, he noted that the wagon looked totally different. The pressurized water not only took off the stains from mud dauber nests and bird droppings but, also stripped the wagon almost bare of its paint and logos. It’s yet one more reminder than the presence of an original painted finish cannot be duplicated and is therefore irreplaceable. I’ll cover more on this element of ‘originality’ in a later blog or feature article as it is increasingly part of collector and enthusiast conversations.

Not to be outdone, it seems vehicle owners from the late 1800’s also needed to be reminded of the importance of proper care of wood-wheeled wagons and carriages. Throughout the Wheels That Won The West® archives, there are regular reminders from manufacturers and industry experts as to how to preserve and protect the looks, functionality and resale value of a set of wheels. With that as a backdrop, we thought we’d share a few common recommendations distributed by multiple 19th century makers as to how to best care for a horse drawn vehicle in use during that time. We’ve added some additional thoughts in italics after several of the itemized points.

1. The vehicle should be kept in an airy, dry coach house, There should be a moderate amount of light; otherwise the colors will be affected. The windows should be curtained, to avoid having direct sunlight strike upon a carriage. (Extended direct and even indirect exposure to light can have significant and irreversible effects on original paint and logo transfers)

2. There should be no communication between the stable and the coach house. The manure heap should also be located as far away from the carriage house as possible. Ammonia fumes crack and destroy varnish, and fade the colors both of painting and lining. Also avoid having a carriage stand near a brick wall, as the dampness from the wall will fade the colors and destroy the varnish. (Dampness and ammonia can have even more devastating effects than the impact mentioned here on paint and varnish. These elements will also work to rust, pit and erode most every part of an early wood-wheeled vehicle)

3. Whenever a carriage stands unused for several days, it should be protected by a large cotton cover sufficiently strong to keep off the dust, without altogether excluding the light. Dust, when allowed to settle on a carriage, eats into the varnish. Care should be taken to keep this cover dry. (Dust-free environments are almost impossible to achieve. Recognizing the enemies of a collector-grade vehicle is the first step to preserving it for generations to come.)

4. Never allow mud to remain long enough to dry on a vehicle or spots and stains may result.

5. While washing a carriage, keep it out of the sun. Use plenty of water, taking great care that it is not driven into the body, to the injury of the lining. Use for the body panels a large, soft sponge; when saturated, squeeze this over the panels, and, by the flowing down of the water, the dirt will soften and harmlessly run off.

6. The directions just given for washing the body apply as well to the under parts and wheels, but use for the latter a different sponge and chamois than those used on the body. Never use a spoke brush, which, in conjunction with the grit from the road, would act like sand paper on the varnish, scratching it and of course removing the gloss.

7. Never allow water to dry of itself on a carriage, as it would invariably leave stains. Hot water or soap should never be used in washing a varnished surface.

8. Enameled-leather tops, and aprons should be washed with very weak soap and water. No oil should be put on enameled leather. (a dilution of Murphy’s Oil Soap with distilled water works well)

9. To prevent or destroy moths in woolen linings, use turpentine and camphor. In the case of a closed carriage the simple evaporation from the mixture, when placed in a saucer (the glass being closed,) will be found a certain cure.

10. Inspect the entire carriage occasionally, and whenever a bolt or clip appears to be getting loose, tighten it up with a wrench, and always have little repairs done at once. Should the tires of the wheels get at all slack, so that the joints of the felloes become visible, have them immediately contracted or the wheels may be permanently injured.

11. Examine the axles frequently; keep them well oiled, and see that the washers (for carriages) are in good order. Pure sperm oil is considered the best for lubricating purposes; castor oil will answer; but never sweet oil, as it will gum up. Be careful in replacing the axle-nuts, not to cross the thread or strain them.

12. Leather top carriages should never stand long in the carriage house with the top down. After raising the top, "break" the joints slightly to take off the strain on the webstay and leather. Aprons of every kind should be frequently unfolded, or they will soon spoil. (In similar fashion, it’s important to remember that wood will expand and contract with variations in temperature and humidity. Beyond efforts to maintain the proper atmospheric conditions when caring for an antique wagon, it’s good not to overly tighten the box rods to allow for slight flexibility during inactive display or storage).

Wednesday, December 12, 2012

Wagons of the Old West – Part II

As I shared last week, there are a number of features seen on many surviving dead axle (sans springs) wagons today that were not traditionally available on early vehicles. One area of difference is that of the primary assembly methods of early wagons.

Most wagon gears from the 1870’s and before are through-bolted. That is, the axles, bolsters and sandboards are connected by drilling holes through them and bolting the sections together. After this timeframe, it is possible to see both through-bolted and ‘clipped’ gears. Instead of using straight bolts to connect the various gear sections, clipped running gears are essentially held together by a series of U-bolts wrapped around the same areas.

While some makers persisted in using the older, through-bolted system well into the 20th century, after the 1880’s, many major manufacturers had made the switch to clipped construction within their higher priced offerings as it was touted to provide stronger support.

Today, there are surviving examples of both types of construction. Was one truly better than the other? The answer often lies within the type of terrain and specific uses a vehicle might be subjected to. Certainly not all wagons needed heavier reinforcement – nor the cost associated with it. Beyond all of these details, the primary point I’m making is that we owe it to future generations to pass along accurate history. Recognizing vehicle facts along with specific features commonplace in certain eras is the first step in helping showcase the true history of America’s earliest transportation industry.

Wednesday, December 5, 2012

Wagons of the Old West - Part I

We’ve all heard the saying, ‘Perception is reality’ but, the truth is, sometimes it isn’t. Over the last twenty years, I’ve heard a lot of statements made about early western vehicles. Some are based in documented facts backed up by primary sources while other remarks are merely a repeat of comments heard so often they’re assumed to be true.

Part of the function of any historian is to help point out false perceptions from reality. After all, while perceptions can fluctuate, true history is fixed. The same thing occurs with the design of early western vehicles. Some technologies on vintage wagons were not available until certain timeframes. Cast thimble skeins, steel skeins, rotating reaches, hub band variations and many other features all had innovative beginnings as they were incorporated into heavy wagons and work vehicles.

Despite these realities, some of my favorite – even well-researched – western theme movies have persisted in employing 20th century-built wagons on early, mid and later 1800’s sets. I’ve covered many of the “general” differences between vehicle brands and time periods within several vehicle presentations I’ve given to groups all over the U.S.

Unfortunately, there isn’t enough space in these short blog posts to cover every variation and distinction. That said, one area that can be briefly examined is the way in which the gear is assembled on an early, dead axle wagon. There are two general forms of constructing a wagon’s running gear (undercarriage). One is the ‘through-bolted’ method and the other technique involves ‘clipped’ gears. I’ll cover more on this in next week’s post. In the meantime, if you have a specific question you’d like answered, feel free to drop us a line at info@wheelsthatwonthewest.com

Wednesday, November 28, 2012

A Sweet Victory

Paging through the history of the 19th and early 20th centuries, there were many areas of the U.S. recognized for producing excellent wood-wheeled transportation. Certainly, the state of Wisconsin was no stranger to accolades for quality vehicles. In fact, it was home to a number of major wagon and carriage makers that are still highly touted today. Among those legendary heavy vehicle brands are Mitchell, LaBelle, Bain, Racine-Sattley, Stoughton, Mandt, and Fish Bros. Also included in this list are makers like Northwestern Manufacturing (Fort Atkinson), Vaughn Manufacturing Company (Jefferson), Smith Manufacturing (La Crosse), White Wagon Works (Sheboygan Falls), and B.F. & H.L. Sweet from Fond du Lac, Wisconsin.

While Sweet was a respected brand – with several wagon-related patents to its credit – the company’s influence was predominantly regional in scope. Large scale state fairs, however, gave strong but smaller makers, like Sweet, a platform on the same level with major national brands. Most of the regional firms had nothing to lose and everything to gain by going head-to-head with the large, national brands in these venues. Thus, in 1888, Sweet dared to step into the competitive limelight with numerous other brands at the Wisconsin State Fair in Milwaukee. Showcasing their craftsmanship alongside some of the most powerful names in 19th century transportation, Sweet ultimately found the risk to be worth the rewards.

Like most state fairs of the time, the event was rife with rivalry. Everything from fine art, leather, and textiles to agricultural products, machinery, and household wares like stoves and cabinetry, were judged and awarded prizes. Not to be left out, manufacturers of carriages, wagons and sleighs were also looking for bragging rights. After all, not only did these prominent competitions draw large crowds but they also provided fodder for a great deal of advertising and promotional hyperbole that could be effectively used for years to come. During this state fair, B.F. & H.L. Sweet took first place in a number of areas including the Best Two-Seated Light Sleigh… Best Fancy Lumber Wagon… Best Double Farm Sleigh… and, Second Best Double Farm Sleigh. They also took top honors for the Best Heavy Logging Sleigh.

Finding the higher quality and best collectible, horse-drawn vehicles from the 1800’s and early 1900’s has become more and more difficult. It’s a multi-part challenge based in part on the ability to both recognize notable survivors as well as understand what elements contribute to the vehicle’s long-term importance. Doug Hansen of Hansen Wheel and Wagon Shop recently shared a nice “Sweet” wagon find with us. This exceptional wagon will date to the early 1900’s. It’s in remarkable condition with strong original paint, transfer graphics on the box, and well-defined wood contours. It will make a solid addition to about any early vehicle collection. Our thanks to Doug for passing along these images.

Wednesday, November 21, 2012

The Weight of the Matter

For thousands of years, gross and net weights have helped determine prices on livestock, products and raw materials. It’s an essential part of business that spans from the smallest to the largest items. As with retailers and wholesale operations all over the U.S. today, certified scales were essential to business transactions throughout early America.

Wagon scales, in particular, were used in both pit and pitless configurations. In each scenario, the wagon would be driven across a large, flat and balanced surface which was connected to the balance beam of a scale. The vehicle would be weighed both empty as well as with the entire load. The difference between the two sums told the scale operator the amount of material in the wagon.

Other than images from century-old advertisements, it’s difficult to find these types of scales today. Since many of these wagon scales sat outside, they have typically succumbed to the deteriorating effects of time and weather.

The circa 1880 scale and housing shown here is part of an interpretive presentation within a small portion of the Wheels That Won The West® collection. Incredibly, the scales were found packed inside wooden shipping boxes, still in their original straw and paper wrappings; a rare, unused find that helps reinforce the legendary purpose and legacy of heavier, wood wheeled horse drawn vehicles.

Wagon scales, in particular, were used in both pit and pitless configurations. In each scenario, the wagon would be driven across a large, flat and balanced surface which was connected to the balance beam of a scale. The vehicle would be weighed both empty as well as with the entire load. The difference between the two sums told the scale operator the amount of material in the wagon.

Other than images from century-old advertisements, it’s difficult to find these types of scales today. Since many of these wagon scales sat outside, they have typically succumbed to the deteriorating effects of time and weather.

The circa 1880 scale and housing shown here is part of an interpretive presentation within a small portion of the Wheels That Won The West® collection. Incredibly, the scales were found packed inside wooden shipping boxes, still in their original straw and paper wrappings; a rare, unused find that helps reinforce the legendary purpose and legacy of heavier, wood wheeled horse drawn vehicles.

Wednesday, November 14, 2012

Lost Military Vehicles

It was the spring of 1864. Years had passed since the onset of civil war in America and time continued to tear at the very foundations of the nation. Bloodshed saturated the soil, families were ripped apart and nefarious ne’er-do-wells roamed the countryside targeting innocents without mercy. It was a period of relentless suffering yet more heartache was still to be sewn as this War-Between-the-States would not officially end for another year.

In south central Arkansas , as with other areas of the country, the Union and Confederate armies were on the move. Echoes of cannons, gunfire and troop movements filled the forests and fields. Even so, on the last day of April, yet another familiar enemy re-entered the front lines. It took the form of threatening clouds and distant rumblings. But, soon enough, the weather would take center stage. As the sky grew dark, lightning flashed and rocketed over the troops, thunder shook the ground and the heavens unleashed a torrent of rain. Walls of water poured onto these war-weary veterans. Through it all, thousands of men and mules and hundreds upon hundreds of four-mule army wagons heaved and slogged their way through the old coach road from Camden to Little Rock . It was a massive effort, full of suspense, void of contentment and all about to come to a head at the Jenkin’s Ferry river crossing.

Here, the northern contingency was in a race. A race for time. A race for advantage. A race for their very lives. Around them, Confederate soldiers were on the offensive. The Union troops, led by General Frederick Steele, were beating a hasty but hard retreat to their closest stronghold in Little Rock . Click here to read the rest of the story on the Wheels That Won The West® website.

Wednesday, November 7, 2012

Horse Drawn Transitions

Throughout 200 years of horse drawn wagon manufacturing in the U.S, there were a lot of innovations and transitions – not just in the vehicle design and production processes but in the development of accessories as well.

While some farmers and ranchers merely cut down the wooden wheels on their wagons and had them placed inside steel rims with rubber tires, others took advantage of skein adaptors that could be bolted to traditional vehicle rims. These types of adaptors could be purchased from a number of outlets including large catalog houses like Montgomery Ward.

Wednesday, October 31, 2012

Wagon accessories…

In a previous blog post, we talked about a number of differences that can set vintage dead axle wagons apart from each other. Among those distinctions are areas that might be termed ‘options’ for these vehicles. Looking through the aged pages of period catalogs, just what was considered to be equipment or feature upgrades with many makers – particularly of farm, emigrant and ranch-style wagons?

Certainly bows and bow staples were accessories. While it may be tempting to look at this feature as somewhat of an age indicator, truth is that it has less to do with age and more to do with region, vehicle purpose/use and vehicle type. There are certainly examples of surviving farm-style wagon boxes from the 1870’s that were never equipped with bow staples.

Other areas of the wagon that were generally considered options and, as such, commanded an upcharge to the base vehicle price are the footboard, brake style & hardware, rough lock chain & associated hardware, drag shoe, spring eat, type of rear end gate, neck yoke, doubletree & singletrees, stay chains, extra box sides, scoop board, tire rivets, tire bolts, larger tire widths, track widths, bois’d arc wheels, steel extension skeins, skein size, reach type (rotating, banded, slip), box tighteners, bolster springs and tongue springs.

Ultimately, elements that constitute an “accessory” can sometimes lead to questions as to why one vehicle has a feature and another doesn’t. It’s an era worthy note as these distinctions play important roles in the provenance, character and overall personality of each set of wheels.

Wednesday, October 24, 2012

Update: 2013 “Borrowed Time” book series

Sometimes it’s hard to keep a secret… especially when elements of legendary western history that have heretofore gone unreported are part of that disclosure. There’s an excitement in those discoveries, though, that naturally creates enthusiasm for sharing details. For those who have honored us with a commitment to the first volume of our new western vehicle book series, I’m confident next year’s edition showcasing Volume 2 will create an especially high level of intrigue. As part of that commitment to our customers, we’re already working on ways to reward your patronage of the first volume with special considerations on follow-up orders for Volume 2.

One of the great aspects of our library of original vehicle images is that it is a living archive with regular additions and discoveries. To that point, within some of our more recent acquisitions is an original cabinet card showing an ox train pulling Peter Schuttler brand freight wagons. The location of the late 1870’s western image was captured on a well-known and historic part of the American frontier (we’ll share more in the book). Ultimately, the timeframe, itself, is such a significant period within America’s western legacy that it gives me pause every time I peer into the photo. Combined with numerous other ultra-scarce images of Peter Schuttler freight wagons and ranch wagons as well as farm and emigrant wagons, this next book in the series is sure to be a strong reference for years to come.

While Volume 2 is slated to feature the most coverage of the legendary Schuttler brand to date, other sections of the upcoming book are also scheduled to include more profiles of different makers and vehicle types as well as technology, vintage photo essays and much more. Clearly, the upcoming edition will have numerous vehicle details not generally available to western enthusiasts and we’re pleased to share so many rare elements previously unseen by contemporary audiences. Thank you, again, to all who have added the first Volume of this series to their collection. As the only series exclusively devoted to wagons and western vehicles, we remain committed to helping shed even more light on such an important part of America’s western frontier.

LAST CALL… As of this posting, there are only a few copies of the first “Borrowed Time” book still available and we recommend you obtain yours now before Volume One is out-of-print. (Due to this extremely limited quantity, please email us first to ensure availability prior to order)

One of the great aspects of our library of original vehicle images is that it is a living archive with regular additions and discoveries. To that point, within some of our more recent acquisitions is an original cabinet card showing an ox train pulling Peter Schuttler brand freight wagons. The location of the late 1870’s western image was captured on a well-known and historic part of the American frontier (we’ll share more in the book). Ultimately, the timeframe, itself, is such a significant period within America’s western legacy that it gives me pause every time I peer into the photo. Combined with numerous other ultra-scarce images of Peter Schuttler freight wagons and ranch wagons as well as farm and emigrant wagons, this next book in the series is sure to be a strong reference for years to come.

While Volume 2 is slated to feature the most coverage of the legendary Schuttler brand to date, other sections of the upcoming book are also scheduled to include more profiles of different makers and vehicle types as well as technology, vintage photo essays and much more. Clearly, the upcoming edition will have numerous vehicle details not generally available to western enthusiasts and we’re pleased to share so many rare elements previously unseen by contemporary audiences. Thank you, again, to all who have added the first Volume of this series to their collection. As the only series exclusively devoted to wagons and western vehicles, we remain committed to helping shed even more light on such an important part of America’s western frontier.

|

Legendary western actor and artist, Buck Taylor recently acquired Volume One of the “Borrowed Time” book series for his own library.

|

Wishing you and yours a wonderful Thanksgiving and Christmas season.

Wednesday, October 17, 2012

The Power of Imperfections

We live in day and age where pressures to achieve ‘perceived’ perfection can easily create challenges. Certainly, it’s a level of expectation that can overlook important considerations when it comes to collecting early, wood-wheeled vehicles. To that point, I believe one of the greatest inhibitors in the early days of my own collecting may have come from the first wagon I purchased. It had such vibrant, original paint that I (wrongly) assumed finding more like it would be as easy as the first one. Years went by and I found myself focusing so closely on the single surface aspect of paint that I’m now convinced I likely overlooked some equally good finds – perhaps much more important – with less than stellar paint. Ultimately, the lesson has been a valuable reminder to continually look closer at the entire vehicle as there are many other factors beyond paint that help create the total worth of these rolling western icons.

Clearly, for collector quality vehicles, not all imperfections are desirable. Some may require professional repair or conservative efforts. However, even in those cases, great care should be taken before wiping a slate clean and totally eliminating every perceived flaw, as there are benefits to some deficiencies, especially those related to certain manufacturing and use blemishes. More specifically, stress and wear marks are not only helpful in ascertaining originality but, likewise, contribute to numerous elements of character, authenticity and provenance.

A good case in point… some earlier vehicle designs have inconsistencies in the cast metal parts – a product of the times as well as the processes employed. Unlike the refined and repeatable methods of assembly line production, original hand forged or cut metal within the makeup of early vehicles may also show variations of angles and shapes. These early-era vehicles are increasingly scarce and preservation of these finds for future generations is just one of the intriguing responsibilities we share as 21st century stewards of history.

Elsewhere, some elements of damaged metal can help share what stresses the parts were subjected to – all part of the important and personal story belonging to a set of wheels. Likewise, striping and paint on many of these vehicles was often done by hand and the less-than-perfect lines will be part of the vehicle’s personality. It’s likely that these hand created lines won’t match perfectly from one side to the other. In many ways, they are one-of-a-kind works of art deserving appropriate respect. Later brand marks were often more consistent as pre-formed stencils and pre-printed logo transfers were used.

Ultimately, when gauging the best approach between preservation, conservation and restoration efforts, it can be helpful to obtain assistance from those who specialize in these evaluations. With any new collector-quality ‘find’ it’s very possible that some work may need to be performed. However, there is a growing recognition from many that measured caution and careful assessments should prevail prior to changing original elements of a vehicle.

With that, we’ll conclude by admitting that there isn’t enough room in this blog to fully discuss every circumstance a person may encounter. Ultimately, that fact brings us back to where we started…The Power of Imperfections… Beyond the opportunity to retain important historical connections and details, surviving features themselves can play a valuable role in reinforcing the individuality of the vehicle while significantly adding to overall intrigue and interest.

Wednesday, October 10, 2012

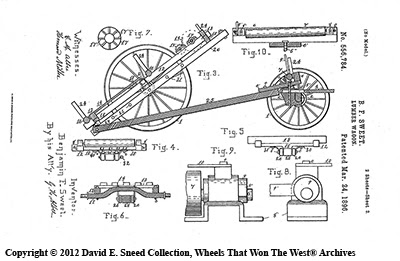

Military Axle Repair Patent

The records in the U.S. Patent Office are overflowing with wagon-related patents, both applied for and granted. However, by the late teens in the 20th century, a shift was taking place and patent applications were beginning to drop considerably. The automobile had come to stay and its impact could be seen in sales as well as within the increasing lack of patent submissions for wagon parts and designs. Times were certainly changing. Even so, there remained enough uses for - and users of – wood wheeled vehicles that some individuals and businesses were still actively pursuing protection of their related ideas.

While the idea sounds plausible, it would be interesting to see effects of its actual use as well as any data showing the durability and long-term soundness of such a quick fix within challenging terrain. At best, it seems a short term solution that might have additional functionality trials.

That said, some elements of this idea have evolved into successful practices today. In fact, many modern trailers are designed with integrated jacks and separate spare axle spindles – new twists on an old idea. Ultimately, it seems that, no matter the era, the need to be prepared and keep moving forward remains essential to both individual progress and national security.

Wednesday, October 3, 2012

National Stagecoach & Freight Wagon Association

We recently received a notice from the National Stagecoach & Freight Wagon Association that they will be holding their 6th Annual Conference in Virginia City, Montana from July 10th - 14th, 2013. The gathering will include a tour of the Nevada City wagon collection along with a number of feature-length vehicle presentations and many more activities.

As a bonus, Virginia City will also be celebrating their 150th Anniversary and, with so many plans in place, the event promises to capitalize on a wealth of western history. Visit the NSFWA website for more details at www.stagecoachfreightwagon.org

While we're on the subject of notices, we also received word from another group out west of an upcoming event. As part of that update, we'd like to send our congratulations to Chandler , Arizona

For more details on the Chandler Centennial Celebration and the November 10th cookoff, visit their website at www.chandlermuseum.org/chuckwagon or give them a call at 480-782-2717.

Wednesday, September 26, 2012

Weber Wagons

I spoke to a gentleman a few weeks ago who asked whether a Weber wagon box would normally be found on a McCormick-Deering running gear. It’s a great question and one that cuts to the heart of how things were done back in the day. Oftentimes today, collectors look for the perfect original vehicle… One with strong paint and logos, no unsoundness in the wood and a world of accessories that somehow managed to stay with the wagon over the last century. Truth is, there is almost always a compromise to those wishes.

Wednesday, September 19, 2012

Wagon & Western Vehicle Auctions

Whether selling, buying or attending as a spectator, early wagon and vehicle auctions are always interesting for a number of reasons. Not the least of which is that they give us an opportunity to examine and potentially learn more about these vintage wheels. There can be dozens of brands, vehicle types, construction methods and manufacturing eras represented. As a result, each vehicle can carry a wealth of potentially valuable information just waiting to be discovered.

Often, the early vehicles at these events will have some type of change or adaptation from their original production design. Once the levels of originality and authenticity have been established, though, it’s easier to spot distinctive features specifically related to the brand… and, while a visual dissection of each set of wheels usually takes some time, the larger number of vehicles on site makes these locations a great place to conduct side by side evaluations of not only different brands but those from the same maker as well. Inevitably, there will be differences that help us to better understand the vehicle and more readily recognize important features.

To that point, I often receive queries asking how a particular maker labeled their vehicles. It’s a difficult question to answer because – like today – those standards tended to change over time as well as between different models and regions of use. Not long ago, I had someone ask if a particular logo from a Weber wagon was indicative of an older design. In this case, it was not. I’ll give the person credit, though, for recognizing a difference and understanding that there was relevance to these areas. Oftentimes, that’s where the best lessons take place – when we see a distinctive difference and then work to secure an answer reinforced by primary sources.

The next time you’re at a vehicle auction, take some extra moments to look closer at the differences between similar vehicles. It’s a practice that will ultimately – and inevitably – uncover important details that not only help to better understand and appreciate these work horses on wheels but, can also play a key role in preventing buyer’s remorse down the road.

Wednesday, September 12, 2012

Building A Western Vehicle Library

Locating authoritative and well-studied resources covering early wood-wheeled vehicles like stagecoaches and wagons as well as a broad contingent of business, ranch and military transports can be challenging.

After almost two decades of daily research, I still encounter folks looking for that one comprehensive book that covers everything. I’ll admit, it would be nice to have such a piece and while I try to never say ‘never’… truth is, it will never happen. Why? Because with tens of thousands of known makers and even more variations in design and manufacturing methods, the horse-drawn vehicle industry was just too massive to authoritatively and concisely cover in one simple volume today.

My personal pursuit of reliable and documentable information began before the internet had established itself as a household necessity. Early on, I was fortunate to find a used book store that sold western books in their “Americana” section. For years, I frequented this place, occasionally stumbling across a ‘find’ and purchasing it. I learned to comb through the footnotes, endnotes and bibliographies of each of these discoveries in an effort to uncover even more valuable answers and details.

Within a few years, the world wide web had grown to sufficient bandwidth and postings that it began to be more useful in locating primary source materials. (A word of caution and a reminder here that while the internet is full of information, not every posting on-line can be supported by facts.)

To start, grow and more fully develop your own western vehicle library, it’s important to keep a number of points in mind like…

- Dividing your focus into specific categories of interest can prove beneficial as it helps highlight the depth of the subjects. Vehicle types, makers, geographic regions, historic ventures and/or specific time periods are just some of the potential categories to consider.

- Scour bibliographies of books and articles for previously unknown works that may reinforce your interests.

- Subscribe to publications produced by organizations with similar interests…i.e… The Carriage Journal magazine, Farm Collector magazine, Wagon Tracks newsletter (Santa Fe Trail Association), National Stagecoach & Freight Wagon Association, American Chuck Wagon Association and others.

- Ask noted writers, historians and/or groups to recommend specific books. I provided an abbreviated list to the National Stagecoach & Freight Wagon Association a few years ago and I believe it’s still on their website.

- While there are some great contemporary works available today, remember that many early resources for antique wagons and coaches will be out-of-print. You may be successful finding more modern works in places like Amazon.com or Barnes & Noble but, others may require a bit of sleuthing within outlets like Ebay or smaller firms selling collector books and ephemera.

The Wheels That Won The West® Archives started with one book purchased in the mid-1990’s. Today, this extensive resource is made up of hundreds of rare books and even more original catalogs and early sales materials. Combined with thousands of primary source images, the collection has become an essential aspect of our research and ability to share historically accurate details with western vehicle enthusiasts the world over.

Wednesday, September 5, 2012

One Horse Wagons

The first one-horse wagon I owned was a John Deere. With single sideboards, petite hubs, a condensed box size and high, narrow wheels, it wasn’t just a well-balanced and light weight piece of functional art but an equally strong vehicle - ready to take on a host of jobs from the farm, ranch or business it would have supported during the first part of the twentieth century.

Built on a smaller scale, one horse wagons like this and even their smaller ‘pony wagon’ cousins share a similar look and design structure with full-size farm wagons. That said, they’re typically a less common sight and, as such, it’s harder to locate and review survivors from the thousands of brands built during the 18 and 1900’s. Recently, we received several images of a Mitchell brand one-horse wagon.

With roots dating to the early 1830’s, Mitchell carries a strong western heritage. The founder, Henry Mitchell, was born in Scotland and immigrated to America in 1834. Almost immediately after his arrival in the U.S., Mr. Mitchell began building vehicles. From emigrants traveling the plains and early farming on the frontier to the storied work of chuck wagons and heavy western freighters, the Mitchell name carries a legendary legacy.

Wednesday, August 29, 2012

He Drove A Mandt Wagon

As I’ve grown older, there’s more about my family I wish I would have asked before cherished members left for their heavenly reward. Some questions, no doubt, would have had more depth as I looked for greater understanding to my own heritage. Others, though, would have been elements of simpler curiosity and general conversation. Queries like… What’s the most acreage you ever plowed with your mule in a day? Or… How long would a container of milk stay fresh when placed in the cold spring? Or… How old were you when you started driving a team?

Being fascinated with early wagons, I would almost certainly have asked more about the horse drawn vehicles my ancestors drove. My dad has shared several stories, himself, and his dad once told me a particularly interesting account that I’ve never forgotten. Seems he was using his team and wagon to pull up some old fence posts. One, particularly stubborn post would not budge and as the team strained, the chain hooked between the wagon axle and post actually lifted the rear of the wagon up. Once the wheels left the ground, the entire gear and box flipped upside down in an instant. Making matters worse, one of my uncles – a youngster at the time – was in the bed of the wagon. As my granddad told the story, he was still amazed at how fast it all happened but, even more surprised that the adrenalin generated by the emergency allowed him to quickly lift the double box and gear off the ground and rescue his son, bright-eyed but unhurt.

I’ve recorded a few other old family accounts involving wagons – one involving a run-away team and another related to the echo of trace and stay chains as neighboring teams began work every morning. Unfortunately, all that remains of my granddad’s wagon, though, is a lone box rod (found near the old wagon shed by my grandmother and I one fall afternoon) and a single board spring seat; saved only by being stored and forgotten in the cellar for more than a half century. A few years ago, one of my mother’s sisters came across a photo of their uncle in a wagon. Knowing my enthusiasm for this subject, my aunt passed this aged photo along to me. As I peered through the magnifying loupe into the faces of family I never had the privilege of knowing, I found myself staring intently at the wagon as well. Scanning and enlarging the near century-old image helped to bring out more details. Almost instantly, the features of a Mandt brand wagon began to surface; the tubular bolster standards, hardware, faded paint and lettering all bore witness to this legendary maker.

In so many ways, the pace of life today can overlook the depth and fulfillment of simpler pleasures and family connections. I’ll likely never know what brand of wagon any of my grandparents owned. But, I now know, there was a great uncle that drove a well-worn legend on wheels. Its name was Mandt.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

+copy+with+text.jpg)

+sized+with+text+copy.jpg)

+-+sized+-+with+text+copy.jpg)

+copy.jpg)