The Wheels That Won The West® Collection

of early vehicle literature includes details on a number of horse drawn vehicle

types. The styles we predominantly focus

on are those within the farm, freight, ranch/trail, coach, business, and military categories. Looking back over the years of articles and

blogs, I realized that we haven’t covered as many examples of wagons and

associated builders that would be included in the general ‘business’ or commercial

category. So, since many of us seem to be stuck with old man winter for a little longer, we’ll focus on

a company and vehicle built to make the most of the cold.

Many will know of or perhaps remember a

time when refrigeration of food was limited to the chill of a cool, flowing spring or maybe

even a sawdust insulated wooden box. My

dad grew up in the South during a time when those things were common. As a teenager, I helped clean out the old

family spring house (over time the silt accumulates) where they had once kept

fresh milk. I also have an old ice box. It’s a simple design with a top lid and galvanized

metal liner. At one time, blocks of ice would

have been placed inside to help preserve food.

The designs were a precursor to modern refrigerators which didn’t

become prevalent until the 1920’s and later.

I still remember my grandmother asking me to go to her back porch and

get food from her “ice box.” It was an

electric freezer but the term was so rooted in her past that she almost never

referred to it in any other way.

Having true ‘ice boxes’ in a home seems

to have become relatively commonplace in America by 1900, with associated ice

providers making regular deliveries to homes and businesses. One of the industry legends, the

Knickerbocker Ice Company of Philadelphia, harvested, stored, and delivered ice

during the 19th and early 20th centuries.

|

This historic cut shows a portion of the Philadelphia workshops of the Knickerbocker Ice Company. |

Knickerbocker had a long history,

apparently dating to as early as the mid-1800’s. The business was incorporated in May of 1864

and appears to have eventually come under control of the American Ice Company

of New Jersey.† In the mid-1890’s, the

company was reported to have $2,000,000 of invested capital. In similarly impressive numbers, the firm

maintained storage capacity for 1,000,000 tons of ice. The product was delivered to customers

throughout Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Maine with large wholesale clients

being dealers, brewers, and packing houses.

So strong was the business that, distribution of ice to customers in

Philadelphia, alone, was said to have required over 500 wagons and 1,200 horses

and mules. It was a demanding operation

maintained by massive workshops ran by the company. The plant in Philadelphia was manned by

approximately 125 employees and included multiple machine shops, a foundry, tool

works, harness making shop, horse shoeing shop, and a wagon manufactory. The Ice Wagons built by Knickerbocker capitalized

on bright graphics and attractive designs.

They were sold throughout the U.S.; from Texas to California, Maryland

to Georgia, and Illinois to Florida.

|

| This rare illustration from the Wheels That Won The West® Archives portrays a scene from the Paint shop of the Knickerbocker Wagon factory. |

Among the strongest vehicles produced by

Knickerbocker was a 2-horse supply wagon.

It was impressively rated to haul up to 4 tons of ice and gear while

weighing in at just over 2700 pounds. In

the same 1889 catalog, a hand-painted vehicle with murals, labeled as a

“Picture Wagon,” was set on heavy platform springs and designed to carry up to

3 tons. Overall, the two-horse designs

generally ranged from 3,000 to 8,000 pound capacities.

Knickerbocker’s one horse ice wagons included an equally wide variety of

designs with hauling capacities starting at 1500 pounds and extending up to 3500

pounds. The firm even made two-wheeled

ice carts with a capacity of 1,000 pounds.

|

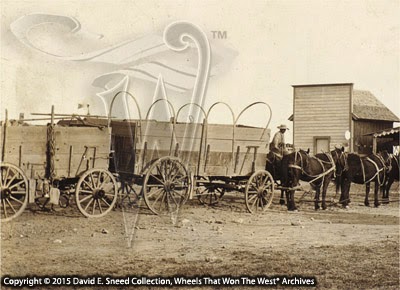

An early promotional image showing a 2-horse Knickerbocker Ice Wagon with a capacity of 4,500 pounds. |

While Knickerbocker claimed to be the

largest producer of wagons, tools, and machinery for moving ice*, it was far

from the only builder of Ice Wagons. A

number of major manufacturers included these designs in their offerings. At the turn of the 20th century, the

famed Studebaker Wagon Company was building Ice Wagons with steel axle sizes

ranging from 1 3/4” to 2 5/8”. The dimensions were typically related to

weight capacities of a particular design.

Wholesale pricing for complete vehicles could range from just over $400

to almost $700; over double and triple of what a farm wagon would have sold for

at the time.

Today, original ice wagons in good

condition can command a much higher tag.

No longer used in the same way, they are cherished for their artful

design, timeframe of service, regional history, maker brand, and the memories

they evoke.

† “Moodys Manual of Railroad and Corporation Securities,” 1921, p. 61-64, Industrials section

† “Moodys Manual of Railroad and Corporation Securities,” 1921, p. 61-64, Industrials section

* “The City of Philadelphia as it Appears in the Year 1894,” p. 205

Please Note: As with each of our blog writings, all imagery and text is copyrighted and may not be broadcast, published, rewritten, or redistributed without prior written permission from David E. Sneed, Wheels That Won The West® Archives.