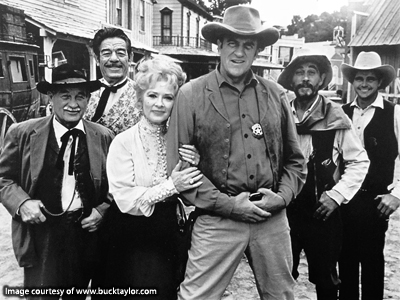

Okay… remember last week? I spoke of a lengthy interview I’d had with well-known

actor and artist, Buck Taylor. In the process, I warned you that this week’s

write-up would be considerably longer. In

that regard, I won’t be disappointing you.

Fact is, the word count is more in keeping with a lengthy feature

article. In the process of writing this

piece, I found myself facing the dilemma of cutting information or separating

the interview into two separate blogs.

Ultimately, neither of those options felt right. It didn’t seem appropriate to overly truncate

the conversation or chop it into sections. There’s just too much information to pass

along – everything from his heroes in the movie industry to upcoming paintings,

advice from his dad, current projects, what he does to relax, and, of course, Gunsmoke. Hopefully, it is of interest. It was certainly an enriching time for

me. So, here goes…

|

It was a full-time job keeping notes while Buck Taylor shared stories from his extensive art and film careers. |

Over the decades, we’ve been fortunate

to uncover a wealth of transportation history tied to the American West. From personal letters written by legendary

wagon maker Joseph Murphy to early western imagery and more than one wagon

dating to some of the wildest days on the frontier, we’ve celebrated a number

of remarkable finds. As many know, it’s

almost always a surprise when these types of special pieces show up. These forgotten fragments not only enrich our

lives but also give a more complete image of the Old West. How much more is still waiting to be

found? Who knows? I may never come across another rare set of

wheels, one-of-a-kind chuck wagon photo, old wooden advertising sign, or early

set of military harness. Even so, I

think the best part of searching for history is the opportunity to meet folks

from all walks of life in all parts of the country. It’s encouraging to share so much common

ground with so many good people.

So, when I got the chance to interview an actor with connections to some of the biggest western dramas to come out of Hollywood, I wasn’t going to miss out. With film and television credits dating from every decade since, and including, the 1960’s, Buck Taylor has deep ties to the American West.

Several years ago, my youngest daughter met Buck and told me, “Dad, I like him. He has kind eyes.” It’s an insight that struck me and I never forgot it. In fact, it’s one of those bits of discernment that reminds me how females often have the advantage over us guys. More than once I’ve noticed how the sensitivity of a lady can pick out things that we crusty males may overlook.

At any rate, as I spoke with Buck, I found him to be someone who made me think more about the people around us and the brief, but memorable, moments we share in life… Someone still seeking to grow and be the best he can be at his craft, whether painting or acting... and someone who remembers the power of encouragement – just as he received that same support from one of his teachers while he was in elementary school.

As of this writing, Buck is 78. Yet, he moves with an energy and alertness that belies his age. When I asked about his early art skills, he quickly recalled how, in the fourth grade, ‘Mrs. Young’ encouraged him to develop his talent. Like so many teachers, she saw something in the boy that was raw but ready. Ready to be shaped and become all it could be. As he talked about those early days, I asked when he first knew he enjoyed painting. He said he was around 4 years old when he began to paint. He quickly followed up, though, saying it’s a passion he really didn’t have a choice in. Emphasizing that point he said, “It’s always been something I had to do.” I’ve heard that type of comment from creative folks before. God puts things in us that just have to come out.

As it turns out, Buck wasn’t the only one in his family with a penchant for painting. He mentioned that his aunt was a fashion illustrator for newspapers and his mother’s father was an oil painter. His father, Dub Taylor, was an artist in his own right as one of Hollywood’s most talented and memorable character actors. When it comes to inspiration for his own paintings, Buck was open about his faith, giving credit to God.

Highlighting his own experiences as well

as events straight out of the pages of history, the paintings hold a wealth of

stories. The basis for many of those

stories was cultivated from an early age. He described his growing-up years as

“fascinating.” As a boy, he remembers

being on major movie sets with his dad and the likes of Jimmy Stewart, Ben

Johnson, and so many other notable stars.

Seeing such elaborate productions with everyone playing different

roles, young Buck enjoyed seeing imaginary worlds come to life. As he was continually exposed to those western

sets, horses, wagons, stagecoaches, and a world of movie icons, he was

unknowingly being groomed as one of the American West’s most notable

ambassadors.

From John Wayne and Ricky Nelson in Rio Bravo to Jack Palance in a host of features, Buck was influenced by numerous actors. One that he mentioned multiple times in the interview was Burt Lancaster. Even at a young age, Buck said he wanted to emulate Burt; swinging from cliffs and swashbuckling his way into the hearts of theater-goers everywhere. He dreamt of capturing the energy and excitement of his on-screen heroes. Reinforcing that thought, he mentioned that in his early film days he did a fair amount of stunt work, often enjoying that more than acting.

According to Buck, it took 6 days to shoot a single episode of Gunsmoke. With credits on 174 of those episodes, that’s a lot of time in the saddle - so to speak. From other serial westerns to more modern shoot-em-ups, he’s played his share of bad guys as well. Still, he confided that his personality on Gunsmoke is much closer to “who I really am.” That character, Newly O’Brien, was always polite, respectful, and focused on doing the right thing.

|

"Over the years, Buck Taylor has shared numerous artistic tributes to his friends and fellow actors from Gunsmoke." |

One of his favorite acting experiences

was the shooting of “Cattle Annie and Little Britches.” Among others like Rod Steiger, Scott Glenn, and

Diane Lane, it starred one of his greatest heroes – Burt Lancaster. Filmed in Mexico, Buck said that the cast

actually camped and lived together for 2 weeks prior to the start of

shooting. They wore the same clothes

they would be filmed in later and had a true opportunity to ‘get into

character’ while also getting to know each other before production began. In his words, “It was a great way to start a

film.”

His latest movie appearance is a flick entitled, “Hell or High Water.” I haven’t seen it but it has received good reviews from a number of sources. Roughly, the film outlines the challenges of a family trying to make good in the world while other forces are intent on taking away their hope and property.

I asked Buck to share the best advice he ever got from his dad related to acting. He immediately replied, “Make sure you look the part. Dad always said that acting was 10% talent and 90% looking the part.” Anyone who’s ever watched Dub Taylor at work knows he was a master at ‘looking the part.’ It’s a reference that reinforces the importance of an actor bringing a character to life.

I saw this same desire to re-create history literally leap out of Buck as I shared a few of our period chuck wagon photos with him. As he looked at the images, one old photo included a group of well-worn cowboys. With their horses as a backdrop, they had gathered around the centerpiece of the roundup – the chuck wagon. As Buck surveyed the group, he pointed to one of the cowboys and exclaimed, “That’s who I want to be!” There was a light in his eyes that reminded me of times when I was a kid picking out someone in a movie that I wanted to be. In this case, Buck’s pure and reactionary thoughts reflected how truly committed he is to having his art imitate real life.

|

Buck examined an early roundup scene digitized from an original photo in our Wheels That Won The West® Archives. |

Having such a busy schedule of film projects, art shows, and promotional appearances, I asked him to share his favorite form of relaxation. He described his house in Texas. Sitting on a bluff facing west, overlooking the Brazos River, he verbally painted a scene with him sitting alongside his wife, Goldie, who he credits as being the love of his life. He said he enjoys watching the sun go down and seeing God paint another masterpiece in the sky. In fact, as accomplished as he is, Buck was even more complimentary toward his wife of 21 years; admitting that she’s both smarter and a better rider than him.

As we talked, he shared some thoughts about one special painting that he’s yet to start but has been contemplating. His description was as vivid as his art. The colors, contours, and mood on the untouched canvas were easy to visualize. He asked me to imagine four equine tied up outside the Long Branch saloon. One, he said, is a mule, two are saddle horses, and the other is hitched to a buggy. As he described the scene, it was clear that the idea was rich with symbolism. He mentioned that the setting takes place at night and said that we can see the oil lamps burning through the windows of the saloon. “Oh, yeah,” he said, “and it’s softly snowing.” As he continued the description he shared that the painting doesn’t literally mention who’s inside but, as you look at it, you realize there are some special friends just beyond the door – Matt, Festus, Doc, Newly, Miss Kitty, and Sam, the bartender.

As he opened up about the painting, I saw a transformation take place. There was that light in his eyes again; an excitement and real connection to the piece. Likewise, his description made it real. I could see it. In fact, I could practically feel the cold air and then, walking toward the building, a brief pocket of warmth beckoning me closer to the door. As the small flakes floated down, they left a light dusting on the ground while simultaneously conforming to the shape of the saddles and contrasting against the black, folding top of the doctor’s buggy. The entire scene was one of calmness and tranquility. There was beauty and richness in this quiet reflection on an otherwise ordinary sight. There was also an element of finality to the art; a dénouement of lives well spent and character duly rewarded.

Lastly, I asked him if anyone ever refers to him as “Walter?” It’s his given name but, I’ve never heard anyone reference him that way. He looked away during the question and as I waited for an answer, he became uncomfortably quiet. Then, he looked straight at me, tightened his lips, and lowered his head. I waited, not knowing what to expect. Then, slowly looking up, he feigned a scowl and sternly said, “NO!” As I wondered how to respond, a smile spread over his face and we both laughed, sharing in the joke. This Hollywood star has worked and been friends with some the biggest names on the silver screen. He’s traveled extensively, been lauded with awards, and holds immense talent. Still, he carries a down-to-earth, very approachable personality with a quick wit and engaging sense of humor. In a word, he’s real.

One thing had become even more noticeable to me as I wrapped up the interview. It was the very thing my daughter had mentioned years earlier… the strength of his ‘kind eyes.’ I saw them as countless people would walk up, listening while we were talking. As he noticed each person, he asked to be excused so he could take interest in them. Many had their own stories and Gunsmoke memories to share. Each time, I waited my turn to continue the interview. It dawned on me that it would be hard to know how many lives Buck and his fellow actors have touched from that one show.

The interview took place in the middle of his art exhibit at Silver Dollar City in Branson, Missouri. During my flurry of questions, there was a moment when a child could be heard crying. Buck raised up and stepped in her direction, clearly concerned and ready to assist if needed. At that point, it occurred to me that Buck Taylor isn’t really an actor at all. After all, an actor has to practice his lines and rehearse a role. Yet, Buck is just who he is. A true cowboy, military veteran, and western hero; not playing a role but, more often than not, just being himself. While I waited for him to return from a visit with another fan, I drifted back to a Saturday evening at my grandparent’s country home. It was summertime. The rhythmic chorus of cicadas, crickets, frogs, and an occasionally whippoorwill filled the warm night air. The sky was clear. I had never seen it so full of stars. I could smell the dust blowing off the dirt road in front of the house. In my mind’s eye, I stepped up on the front porch and peered through the old multi-pane windows. There, in the living room, another episode of Gunsmoke was coming to a close. On the floor was that 9-year-old boy I used to be. As the credits rolled, I watched the kid push himself up and look back at his grandpa. They made eye contact and both smiled; each fully content with the time they shared, company they kept, and memories they were making. These are the ties that bind, the core of a nation blessed with freedom and the reason so many have given so much in defense of this land.

Ultimately, we’re all a reflection of what we do with the talents, experiences, and opportunities we’re gifted with. We have one chance in this life to make a difference. One chance to leave an endearing legacy. My personal thanks to Buck (and others) for stepping away from the importance of business and limelight of celebrity to make one more memory.

After appearing in hundreds of television and movie productions and finishing more paintings than I can count, it would seem that the man has made an indelible mark on the spirit of the American West and creativity in general. When I asked him how he wanted to be remembered, he responded as if his elementary school teacher, Mrs. Young, was still talking to him. He shared a bit of advice that he said he’s always tried to adhere to… “Never quit and never give up.”

Well said, Buck. Well said.

|

|

Please Note: As with each of our blog writings, all imagery and text is copyrighted with All Rights Reserved. The material may not be broadcast, published, rewritten, or redistributed without prior written permission from David E. Sneed, Wheels That Won The West® Archives, LLC