Researching

America’s first transportation industry isn’t always an easy task. The whole process can be extremely

time-consuming and exasperating; cold trails running this way and that...

hearsay, rumors, misinformation, dead ends and mysteries running rampant. Truth is, so much of what once was common

knowledge has passed into a hard-to-track category so vague, unfamiliar, and

fruitless, we often label it as a four-letter word... Lost. It’s a box canyon we’re continually fighting

our way through and, along the way, celebrating when another piece of the

puzzle is found.

One

of the portals offering insights and clues into days-gone-by is that of

obituaries. While it might seem a bit on

the morbid side at first, these period documents can contain life overviews that

are otherwise difficult to find. Inside

those information particulars, it’s not unusual to come across nuggets that help

define, date, and even authenticate vehicles.

With tens of thousands of carriage and wagon makers dotting the American

landscape, we’ll never get to the bottom of the history of each one but, our

ultimate goal is to help introduce enough folks to these stories that we save

as much of our past as possible.

|

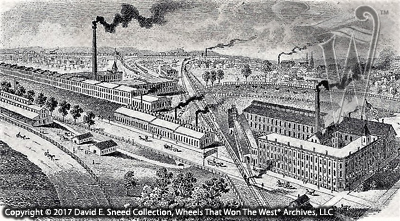

This factory illustration shows the E.D. Clapp factory in the late 1880’s |

To

that point, E.D. Clapp (Emerous Donaldson Clapp) may not be very well-known to

many of today’s early vehicle enthusiasts.

Nonetheless, he and his businesses were an important part of America’s

horse-drawn vehicle world during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. From wagon-making to manufacturing carriage

and saddlery hardware, hauling coal, and running stage lines, Mr. Clapp was an

instrumental force in our first transportation industry.

In

an effort to share a bit more about this seldom-profiled manufacturer, I

thought we’d take a look at the legacy of the man through the words published

after his death in the July 1889 issue of The

Hub. The story was originally

written for The Bulletin in Auburn,

New York in that same month...

“The deceased

was born at Ira, this country, November 12, 1829, and was consequently 60 years

of age. He was educated at the district

school and at Falley Seminary, at Fulton.

In 1851 he moved to Ira and built a small shop and began the manufacture

of farm wagons and other vehicles. He

continued doing business in Ira for four years, employing six men and turning

out about twenty-five wagons per year, besides a number of light

carriages. In 1855 he leased his wagon

shop and began running a stage line between Oswego and Auburn, carrying a daily

mail from that year up to 1880. He was

uncommonly successful in bidding for mail carrying contracts, and until 1865

gave the greater share of his attention to carrying out and sub letting the

same.

In 1856, when

Auburn contained only 7,000 inhabitants, he removed here, and has since been

one of the most active and successful businessmen in the community. He carried on a livery business on Garden and

State streets, for several years until 1867, when he sold out and concentrated

all his energies in the manufacturing business.

In 1864, he leased a small shop on Mechanic street, and having a patent

on a thill coupling for vehicles he began manufacturing the same. This was the first institution which

manufactured carriage hardware in Auburn, and, as time progressed it grew to be

one of the largest factories of the kind in the United States. The business grew to such proportions that in

1867 it was removed to a new factory on Water street, the firm name being Clapp,

Fitch & Co. In 1873, Mr. Fitch retired,

and the business was continued by Mr. Clapp and F. Van Patten, under the firm

name of E.D. Clapp & Co. In 1873 the

site on the corner of Genesee and Division streets, now occupied by the large

shops of the company, was presented to the firm, and sufficient money was

subscribed to build the foundation of the present factory. In 1876 the business was incorporated under

the name of E. D. Clapp Mfg. Co., with a paid up capital of $150,000. In 1880 Mr. Clapp organized the Auburn

Wrought-Iron Bit and Iron Co., with a capital of $60,000, and in the same year

the E.D. Clapp Wagon Co. Limited, turning out the first wagon in April

1881. The company have also done an

extensive business in coal, handling from 15,000 to 20,000 tons a year. The various shops under the management of Mr.

Clapp at the time of his death gave employment to about 600 hands...”

|

The E.D. Clapp Wagon Company Limited built its first wagon in 1881. This rare, surviving card was created to promote the brand’s offerings of iron axle and thimble skein wagons. |

Filled

with dates and other business details, Mr. Clapp’s obituary provides an

abundance of leads, helping fill in the gaps of this part of history. We know from other sources that, in 1876, Mr.

Clapp and his business partner, Frederick Van Patten, were awarded another

patent for a quiet, non-rattling thill coupling. We also know that the company produced a variety

of vehicles, including farm, freight, coal, lumber, and ice wagons as well as

bob sleighs. They ceased building wagons

around 1890, focusing on the expertise they had gained in the drop forging

industry. Even so, the same “Auburn” brand and logo was carried on by the

Auburn Wagon Company first in Greencastle, Pennsylvania and then moving to

Martinsburg, West Virginia, with its charter there issued in March of 1897.

E.D.

Clapp’s firm was sold in 1958, marking the first time in more than a century that

it was not owned by a member of the Clapp family. Over the decades, the company had provided

hundreds of thousands of hardware parts for buggies built by a host of

legendary builders. Included among those

parts were fifth wheels, axle clips, king bolts, clevises, shaft couplings,

doubletree clevises and staples, spring clips, shaft and pole eyes, and more.

During

the Civil War, they provided forgings for guns as well as for wagons. They supplied additional hardware for wagons

in the Spanish-American War. Likewise,

during WWI, WWII, and the Korean War they provided forgings for trucks, tanks,

planes, warships, torpedoes, and countless other military needs.

Today,

too many folks walk by the old wheels of yesterday, passing off the silent

survivors and never asking what real history they’re connected to or hold. Each is filled with information and the

stories they tell help us reassemble the road map to our past. Most of the time, we only scratch the surface

when we examine a vehicle’s provenance.

Digging a little deeper, though, can add greatly to our appreciation of

the past while enriching the present and passing along an important heritage to

future generations.

Please Note: As with each of our blog writings, all imagery and text is copyrighted with All Rights Reserved. The material may not be broadcast, published, rewritten, or redistributed without prior written permission from David E. Sneed, Wheels That Won The West® Archives, LLC